How I Make a Picture, and why it Matters

Today I want to write about my process in making a digital illustration. And by way of conclusion, I’ll also comment on process itself, and why I think sharing a process for making is more important than ever.

I tend to make a digital illustration in five steps - Research, sketching, drawing, painting and final tweaks. Let’s go!

1) Research

The first stage of a drawing often involves no drawing at all. It’s where I think about what I want to draw, and then browse Pinterest or other image galleries for references and inspiration. It’s very easy to get bogged down here, so I try not to get too hung up on finding the perfect reference. If there are particular character poses I’m after, I’ll generally focus on that. But I’m also thinking about costumes, colours, and what other elements and objects will feature in the picture. If I want to start a drawing first thing in the morning, I try to have my references sorted the night before (though I’m not always that organised).

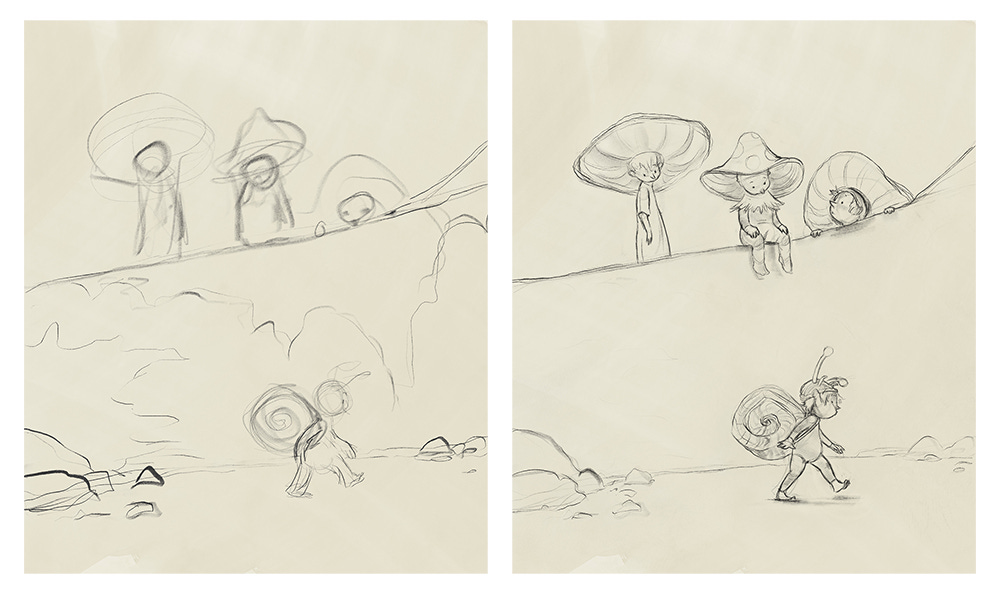

2) Sketching

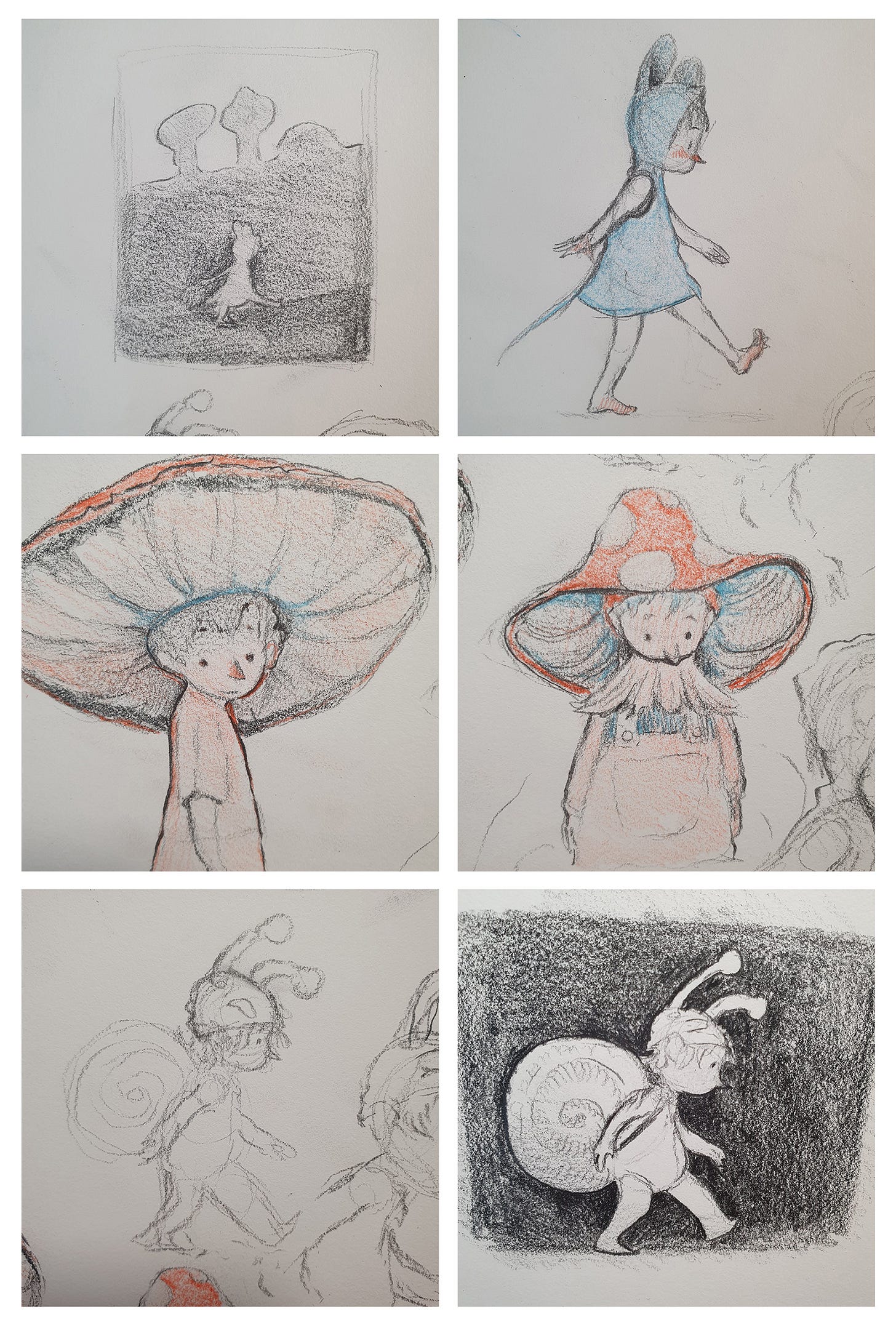

Once I have the references I need, I start sketching. Most of the time I’ll jump straight into Procreate for this. But sometimes I like to start on paper. Working on paper forces you push past your mistakes and keep moving, rather than standing still to endlessly erase and revise. I end up with a lot of garbage but it’s good garbage - I like seeing my mistakes and how I tweak ideas along the way. Initially, I planned for the main character of this piece to be a child dressed as a mouse. But I changed my mind along the way and made them a snail instead. This stage is basically about thinking it through, and seeing quickly what might or might not work.

3) Drawing

Once I know what I’m doing a bit more, I’ll go into Procreate (if I’m not already there), and start working towards the finished linework. If I have a pencil sketch that I really like, I might photograph it with the iPad and trace it. But usually I’ll start again on a blank canvas with any previous sketches simply as reference.

When drawing linework, I like to use pencil, charcoal and pastel brushes. I start with a lighter grey, and build up to blacks as I go. I use a kneaded eraser to erase lines softly, and almost never entirely. This drawing is actually quite tight, but generally I like leaving small traces of mistakes. With that in mind, I also use smudge brushes extensively, and often in place of the eraser. If I want to re-do a line or shape, I might smudge it out and draw over the top. All this serves to build up texture, movement and spontaneity. Sometimes if I finish the contours a little too tightly, I’ll go through at the end and erase and smudge away what doesn’t need to be there. I’ll add a bit of charcoal or pastel texture to indicate tone and shadow, but I don’t go overboard - a lot of this can be done in the painting stage.

Most often I’ll spend a lot of time in the drawing stage. I’ve gone through phases where I draw minimally and do most of the work in the painting stage, but I can never quite get the effect I’m after. I’m more comfortable drawing than painting, and so I tend to let the linework carry most of the picture’s success. In this piece, the drawing is simple, and didn’t take me too long. I’m leaving a lot of space for blocks of colour and texture

I use an assortment of Procreate brushes from various purchased packs, but for lines like this I mostly use charcoal and pastels from Lane Brown. You can find his brushes here.

4) Painting

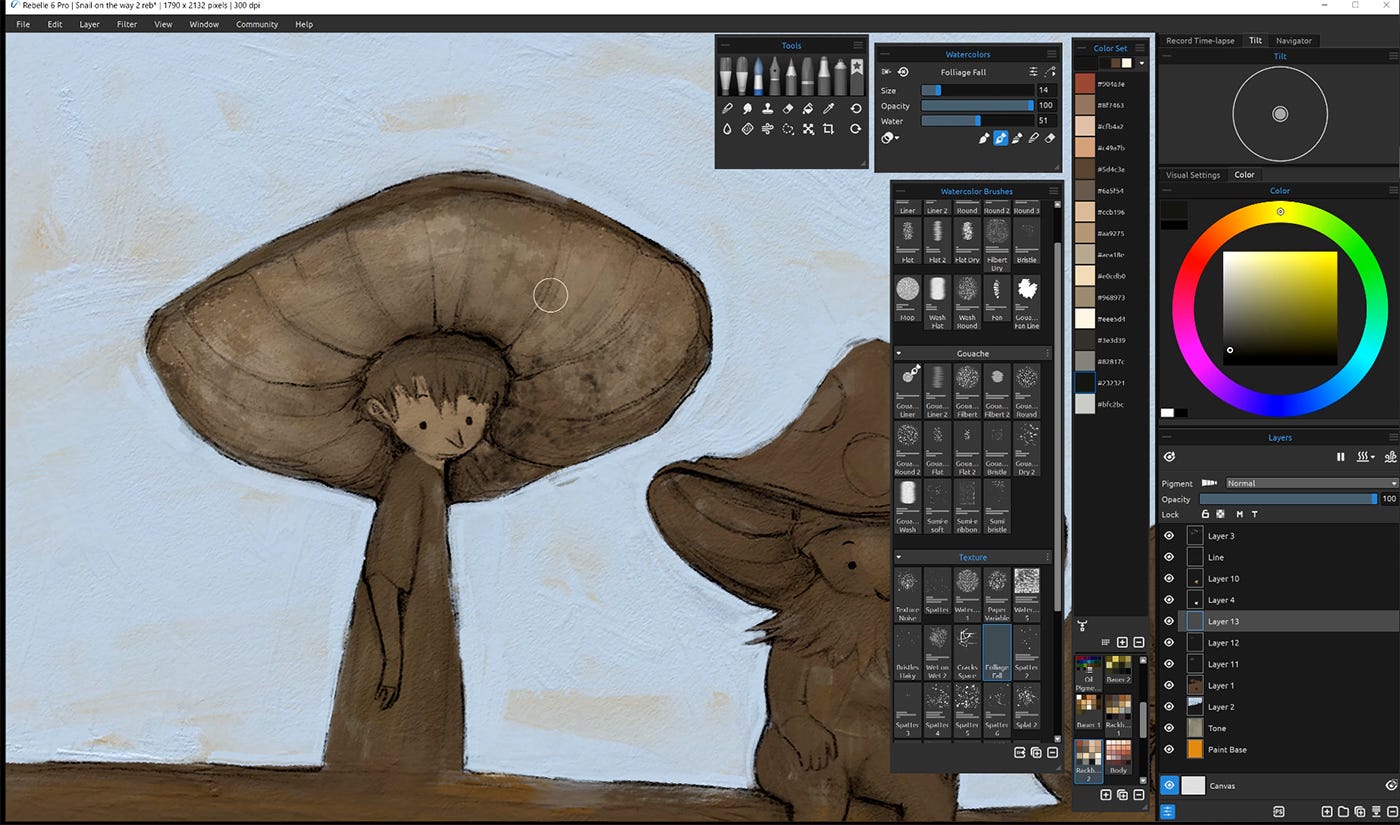

For a very long time I only painted in Photoshop. I knew the application well, I liked the brushes - it was a comfort zone. Then (a few years ago now) I finally got myself an iPad, and I completely fell in love with Procreate. The brushes didn’t quite behave the way I wanted them too, but the app more than made up for that by how truly pleasurable it was to draw in. I now frequently finish entire projects in Procreate, including whole picture books for publishers. But I recently started experimenting with a painting program called Rebelle, by Escape Motions.

Rebelle is a PC/Mac application and I use it on a Wacom Cintiq Pro 16. It’s really quite extraordinary in the way it imitates the look and feel of traditional wet media. I use the watercolour brushes for the bulk of the colouring, and the oil brushes to build up texture and add highlights and accents. Partly because of the way the brushes work and partly because I’m still learning how to use it, I work slowly in Rebelle. But I don’t mind - not for personal work. It’s nice to slow down and concentrate on what I’m doing; fumbling along and often being surprised at what happens.

In this picture, I didn’t use the watercolour brushes to their full potential. You can control how much water is applied to both the brush and the canvas, and if you use a lot, the colours will run and blend and granulate and do all kinds of brilliant things. I’ll demonstrate this more in future posts, but in this one I kept the canvas dry and the colours consequently quite controlled.

I like muted colours. I tend to gravitate towards browns, greens, yellows and red accents. Because I know what I like, I didn’t plan the colour palette beforehand; I just followed my instincts. I knew I wanted the snail fellow to pop against a dark background, and the silhouettes of the mushroom fellows to read starkly against the bright sky. Other than that, I made it up as I went. At some point in the process, I decided to add some opalescence to the sky and snail shell. I think it works! A sneaky way of getting colour in there without impacting the overall brown. I should say that for client work, I would put considerably more thought into colour, and would likely be working from a pre-planned palette.

Another notable feature of Rebelle is what it calls NanoPixel technology (available in the Pro version). It’s basically an advanced upscale function that allows you to export a file up to 16x the canvas size with little-to-no noticeable loss of quality. This is an important feature, as the software uses a lot of computing power. My PC is pretty decent, but when working at full print size, the watercolour brushes in particular become very laggy. Working at 50% scale, however, fixes that issue. The brushes work faster, and I simply export at twice the pixels (and it still looks great). That said, I’ve been too nervous to work at 50% scale for client work. I think it would be fine, but I haven’t yet compared print tests to see if I can tell the difference between a piece enlarged and one painted at full scale. Stay tuned for further comment!

All up, I was fiddling around in Rebelle for about four and a half hours on this picture.

5) Final Tweaks

After I’ve finished painting in Rebelle, I’ll export a TIFF and open it in Photoshop (yes, my old friend). While I don’t draw much in Photoshop anymore, I do still like finishing up in there. I adjusted the brightness and contrast, boosted the saturation a touch, sized the canvas appropriately and exported the final files - some for print, some for screen. On other projects I might play with the colours a bit too, but for this one, apart from a bit of saturation, I left the colours as I painted them.

I titled this post, “How I Make a Picture, and why it Matters". So why does it matter? Here, I’m not writing about my process specifically; I’m writing about process in general. I want to comment about why having a process - any process at all - is important.

Over the past year, most people have become aware of the awesome and bewildering rise of AI text-to-image generators like Midjourney and DALL.E 2 by OpenAI. There are legal and regulatory hurdles on the horizon for these companies, but the fact remains that the technology is here to stay. Incredible and beautiful pictures can now be generated by anyone with increasing speed, accuracy and customisability. If you’re an artist who makes purely for the love of craft, this takes nothing away from you. Process obviously matters because that’s where the joy and reward is. But if you’re a commercial artist who sells work as a product or service, be aware that the whole art economy is going to change. But I’m not writing to frighten or depress you. I have some encouragement, I promise.

The value of a finished picture is going to diminish. We’re going to be swamped with so much beautiful imagery (made instantly without any making at all), that we won’t be impressed, awed or even particularly interested. When something is easy to do, we don’t value it. I’d rather phrase it like this: people will always value things that are hard to do. From now on, people won’t know whether a picture was hard to do or not. Not unless an artist shows them. That’s why I’m saying that process matters. If you’re a professional artist, I believe your finished work is no longer your primary product - your process is. If something is hard to do - if it takes time and practice and is connected fundamentally to individual human endeavour - then it has a story. And people like stories.

So if you make things, tell us how you make things. Show us. We want to know, because in an age where so much is easy, we’re utterly fascinated with effort; with people who try and make and master. We’re fascinated with stories. With how a nothing becomes a beginning and then a struggle and an end. Pictures themselves don’t matter as much anymore. But people do. And process matters more than ever.

I love your perspective on how process will have a whole new importance to it - thank you for this outlook! Also, those characters are divine!

And I'm more than happy to see processes! So now you are back to the pc right? When using rebelle. I remember I had painter which had also the wet controls for some brushes and so many others. I never mastered it tho.

Didn't know the shell of the snail had colors or well I rather ignore them until seeing the process, how delightful